Chapter 7: Critical and Creative Thinking

Overview

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define critical thinking

- Describe the role that logic plays in critical thinking

- Describe how critical thinking skills can be used to evaluate information

- Apply the CRAAP test to evaluate sources of information

- Identify strategies for developing yourself as a critical thinker

- Identify applications in education and one's career where creative thinking is relevant and beneficial

- Explore key elements and stages in the creative process

- Apply specific skills for stimulating creative perspectives and innovative options

- Integrate critical and creative thinking in the process of problem-solving

Critical and Creative Thinking

Critical and Creative Thinking

Critical Thinking

As a college student, you are tasked with engaging and expanding your thinking skills. One of the most important of these skills is critical thinking because it relates to nearly all tasks, situations, topics, careers, environments, challenges, and opportunities. It is a “domain-general” thinking skill, not one that is specific to a particular subject area.

What Is Critical Thinking?

Critical thinking is clear, reasonable, reflective thinking focused on deciding what to believe or do (Robert Ennis.) It means asking probing questions like “How do we know?” or “Is this true in every case or just in this instance?” It involves being skeptical and challenging assumptions rather than simply memorizing facts or blindly accepting what you hear or read.

Imagine, for example, that you’re reading a history textbook. You wonder who wrote it and why, because you detect certain biases in the writing. You find that the author has a limited scope of research focused only on a particular group within a population. In this case, your critical thinking reveals that there are “other sides to the story.”

Who are critical thinkers, and what characteristics do they have in common? Critical thinkers are usually curious and reflective people. They like to explore and probe new areas and seek knowledge, clarification, and new solutions. They ask pertinent questions, evaluate statements and arguments, and they distinguish between facts and opinion. They are also willing to examine their own beliefs, possessing a manner of humility that allows them to admit lack of knowledge or understanding when needed. They are open to changing their mind. Perhaps most of all, they actively enjoy learning, and seeking new knowledge is a lifelong pursuit. This may well be you!

No matter where you are on the road to being a critical thinker, you can always more fully develop and finely tune your skills. Doing so will help you develop more balanced arguments, express yourself clearly, read critically, and glean important information efficiently. Critical thinking skills will help you in any profession or any circumstance of life, from science to art to business to teaching. With critical thinking, you become a clearer thinker and problem solver.

Critical Thinking IS | Critical Thinking is NOT |

Questioning | Passively accepting |

Skepticism | Memorizing |

Challenging reasoning | Group thinking |

Examining assumptions | Blind acceptance of authority |

Uncovering biases | Following conventional thinking |

The following video, from Lawrence Bland, presents the major concepts and benefits of critical thinking.

Critical Thinking and Logic

Critical thinking is fundamentally a process of questioning information and data and then reflecting on and assessing what you discover to arrive at a reasonable conclusion. You may question the information you read in a textbook, or you may question what a politician or a professor or a classmate says.

You can also question a commonly held belief or a new idea. It is equally important (and even more challenging) to question your own thinking and beliefs! With critical thinking, anything and everything is subject to question and examination for the purpose of logically constructing reasoned perspectives.

What Is Logic?

The word logic comes from the Ancient Greek logike, referring to the science or art of reasoning. Using logic, a person evaluates arguments and reasoning and strives to distinguish between good and bad reasoning, or between truth and falsehood. Using logic, you can evaluate the ideas and claims of others, make good decisions, and form sound beliefs about the world.[1]

Questions of Logic in Critical Thinking

Let’s use a simple example of applying logic to a critical-thinking situation. In this hypothetical scenario, a man has a Ph.D. in political science, and he works as a professor at a local college. His wife works at the college, too. They have three young children in the local school system, and their family is well known in the community. The man is now running for political office. Are his credentials and experience sufficient for entering public office? Will he be effective in the political office? Some voters might believe that his personal life and current job, on the surface, suggest he will do well in the position, and they will vote for him. In truth, the characteristics described don’t guarantee that the man will do a good job. The information is somewhat irrelevant. What else might you want to know? How about whether the man had already held a political office and done a good job? In this case, we want to think critically about how much information is adequate in order to make a decision based on logic instead of assumptions.

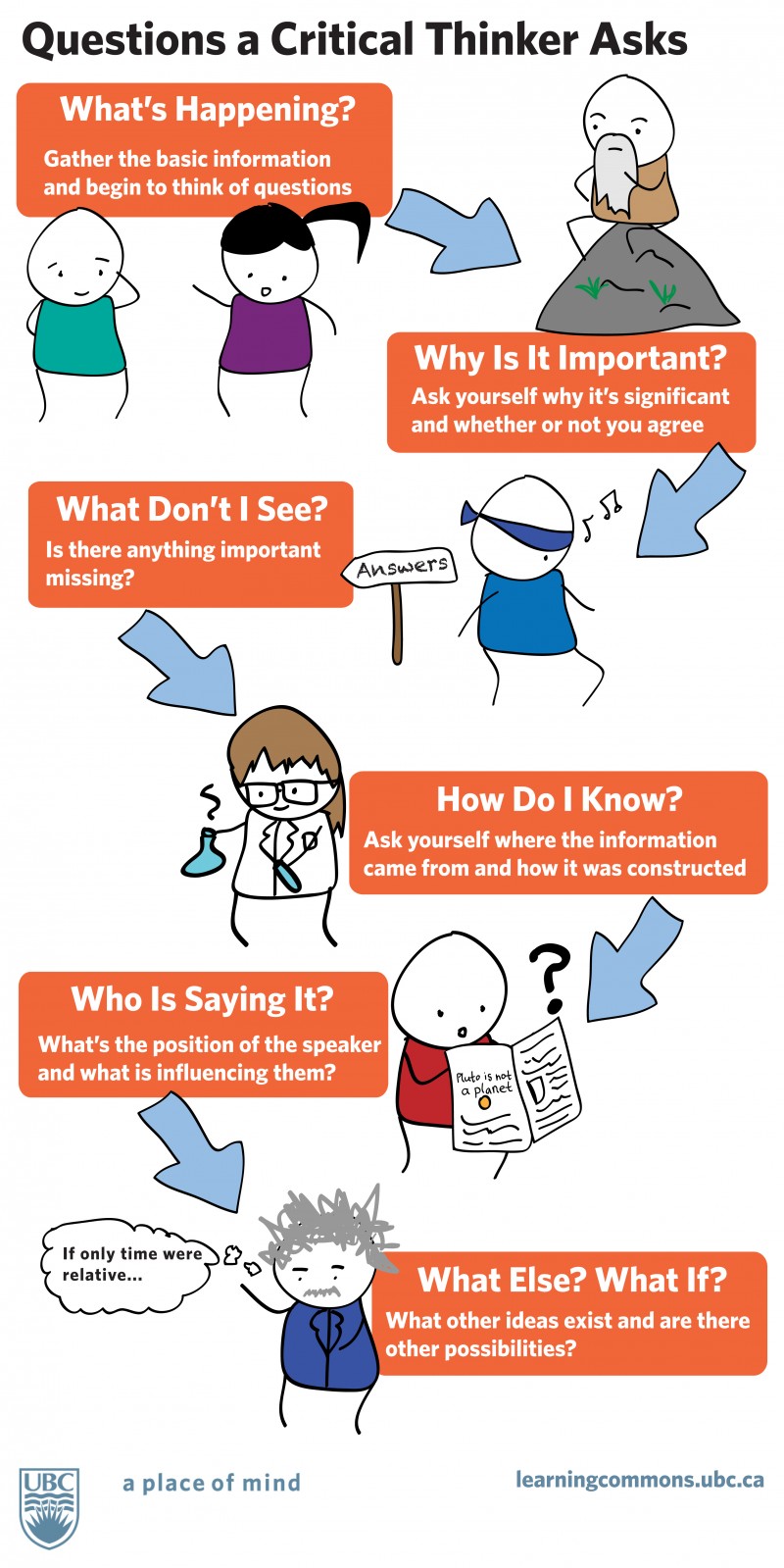

The following questions, presented in Figure 1, below, are ones you may apply to formulate a logical, reasoned perspective in the above scenario or any other situation:

- What’s happening? Gather the basic information and begin to think of questions.

- Why is it important? Ask yourself why it’s significant and whether or not you agree.

- What don’t I see? Is there anything important missing?

- How do I know? Ask yourself where the information came from and how it was constructed.

- Who is saying it? What’s the position of the speaker and what is influencing them?

- What else? What if? What other ideas exist and are there other possibilities?

Figure 1

Problem-Solving with Critical Thinking

For most people, a typical day is filled with critical thinking and problem-solving challenges. In fact, critical thinking and problem-solving go hand-in-hand. They both refer to using knowledge, facts, and data to solve problems effectively. But with problem-solving, you are specifically identifying, selecting, and defending your solution. Below are some examples of using critical thinking to problem-solve:

- Your roommate was upset and said some unkind words to you, which put a crimp in the relationship. You try to see through the angry behaviors to determine how you might best support the roommate and help bring the relationship back to a comfortable spot.

- Your campus club has been languishing due to a lack of participation and funds. The new club president, though, is a marketing major and has identified some strategies to interest students in joining and supporting the club. Implementation is forthcoming.

- Your final art class project challenges you to conceptualize form in new ways. On the last day of class when students present their projects, you describe the techniques you used to fulfill the assignment. You explain why and how you selected that approach.

- Your math teacher sees that the class is not quite grasping a concept. She uses clever questioning to dispel anxiety and guide you to a new understanding of the concept.

You have a job interview for a position that you feel you are only partially qualified for, although you really want the job and you are excited about the prospects. You analyze how you will explain your skills and experiences in a way to show that you are a good match for the prospective employer.

- You are doing well in college, and most of your college and living expenses are covered. But there are some gaps between what you want and what you feel you can afford. You analyze your income, savings, and budget to better calculate what you will need to stay in college and maintain your desired level of spending.

Evaluating Information with Critical Thinking

Evaluating information can be one of the most complex tasks you will be faced with in college. But if you utilize the following four strategies, you will be well on your way to success:

- Read for understanding

- Examine arguments

- Clarify thinking

- Cultivate “habits of mind”

Read for Understanding

When you read, take notes or mark the text to track your thinking about what you are reading. As you make connections and ask questions in response to what you read, you monitor your comprehension and enhance your long-term understanding of the material. You will want to mark important arguments and key facts. Indicate where you agree and disagree or have further questions. You don’t necessarily need to read every word, but make sure you understand the concepts or the intentions behind what is written. See the chapter on Active Reading Strategies for additional tips.

Examine Arguments

When you examine arguments or claims that an author, speaker, or other source is making, your goal is to identify and examine the hard facts. You can use the spectrum of authority strategy for this purpose. The spectrum of authority strategy assists you in identifying the “hot” end of an argument—feelings, beliefs, cultural influences, and societal influences—and the “cold” end of an argument—scientific influences. The most compelling arguments balance elements from both ends of the spectrum. The following video explains this strategy in further detail:

Clarify Thinking

When you use critical thinking to evaluate information, you need to clarify your thinking to yourself and likely to others. Doing this well is mainly a process of asking and answering probing questions, such as the logic questions discussed earlier. Design your questions to fit your needs, but be sure to cover adequate ground. What is the purpose? What question are we trying to answer? What point of view is being expressed? What assumptions are we or others making? What are the facts and data we know, and how do we know them? What are the concepts we’re working with? What are the conclusions, and do they make sense? What are the implications?

Cultivate “Habits of Mind”

“Habits of mind” are the personal commitments, values, and standards you have about the principle of good thinking. Consider your intellectual commitments, values, and standards. Do you approach problems with an open mind, a respect for truth, and an inquiring attitude? Some good habits to have when thinking critically are being receptive to having your opinions changed, having respect for others, being independent and not accepting something is true until you’ve had the time to examine the available evidence, being fair-minded, having respect for a reason, having an inquiring mind, not making assumptions, and always, especially, questioning your own conclusions—in other words, developing an intellectual work ethic. Try to work these qualities into your daily life.

CRAAP Test

In 2010, a textbook being used in fourth-grade classrooms in Virginia became big news for all the wrong reasons. The book, Our Virginia by Joy Masoff, had caught the attention of a parent who was helping her child do her homework, according to an article in The Washington Post. Carol Sheriff was a historian for the College of William and Mary and as she worked with her daughter, she began to notice some glaring historical errors, not the least of which was a passage that described how thousands of African Americans fought for the South during the Civil War.

Further investigation into the book revealed that, although the author had written textbooks on a variety of subjects, she was not a trained historian. The research she had done to write Our Virginia, and in particular the information she included about Black Confederate soldiers, was done through the Internet and included sources created by groups like the Sons of Confederate Veterans, an organization which promotes views of history that de-emphasize the role of slavery in the Civil War.

How did a book with errors like these come to be used as part of the curriculum and who was at fault? Was it Masoff for using untrustworthy sources for her research? Was it the editors who allowed the book to be published with these errors intact? Was it the school board for approving the book without more closely reviewing its accuracy?

There are a number of issues at play in the case of Our Virginia, but there’s no question that evaluating sources is an important part of the research process and doesn’t just apply to Internet sources. Using inaccurate, irrelevant, or poorly researched sources can affect the quality of your own work. Being able to understand and apply the concepts that follow is crucial to becoming a more savvy user and creator of information.

When you begin evaluating sources, what should you consider? The CRAAP test is a series of common evaluative elements you can use to evaluate the Currency, Relevance, Authority, Accuracy, and Purpose of your sources. The CRAAP test was developed by librarians at California State University at Chico and it gives you a good, overall set of elements to look for when evaluating a resource. Let’s consider what each of these evaluative elements means.

Currency

One of the most important and interesting steps to take as you begin researching a subject is selecting the resources that will help you build your thesis and support your assertions. Certain topics require you to pay special attention to how current your resource is—because they are time sensitive, because they have evolved so much over the years, or because new research comes out on the topic so frequently. When evaluating the currency of an article, consider the following:

- When was the item written, and how frequently does the publication come out?

- Is there evidence of newly added or updated information in the item?

- If the information is dated, is it still suitable for your topic?

- How frequently does information change about your topic?

Relevance

Understanding what resources are most applicable to your subject and why they are applicable can help you focus and refine your thesis. Many topics are broad and searching for information on them produces a wide range of resources. Narrowing your topic and focusing on resources specific to your needs can help reduce the piles of information and help you focus in on what is truly important to read and reference. When determining relevance consider the following:

- Does the item contain information relevant to your argument or thesis?

- Read the article’s introduction, thesis, and conclusion.

- Scan main headings and identify article keywords.

- For book resources, start with the index or table of contents—how wide a scope does the item have? Will you use part or all of this resource?

- Does the information presented support or refute your ideas?

- If the information refutes your ideas, how will this change your argument?

- Does the material provide you with current information?

- What is the material’s intended audience?

Authority

Understanding more about your information’s source helps you determine when, how, and where to use that information. Is your author an expert on the subject? Do they have some personal stake in the argument they are making? What is the author or information producer’s background? When determining the authority of your source, consider the following:

- What are the author’s credentials?

- What is the author’s level of education, experience, and/or occupation?

- What qualifies the author to write about this topic?

- What affiliations does the author have? Could these affiliations affect their position?

- What organization or body published the information? Is it authoritative? Does it have an explicit position or bias?

Accuracy

Determining where information comes from, if the evidence supports the information, and if the information has been reviewed or refereed can help you decide how and whether to use a source. When determining the accuracy of a source, consider the following:

- Is the source well-documented? Does it include footnotes, citations, or a bibliography?

- Is information in the source presented as fact, opinion, or propaganda? Are biases clear?

- Can you verify information from the references cited in the source?

- Is the information written clearly and free of typographical and grammatical mistakes? Does the source look to be edited before publication? A clean, well-presented paper does not always indicate accuracy, but usually at least means more eyes have been on the information.

Purpose

Knowing why the information was created is a key to evaluation. Understanding the reason or purpose of the information, if the information has clear intentions, or if the information is fact, opinion, or propaganda will help you decide how and why to use information:

- Is the author’s purpose to inform, sell, persuade, or entertain?

- Does the source have an obvious bias or prejudice?

- Is the article presented from multiple points of view?

- Does the author omit important facts or data that might disprove their argument?

- Is the author’s language informal, joking, emotional, or impassioned?

- Is the information clearly supported by evidence?

When you feel overwhelmed by the information you are finding, the CRAAP test can help you determine which information is the most useful to your research topic. How you respond to what you find out using the CRAAP test will depend on your topic. Maybe you want to use two overtly biased resources to inform an overview of typical arguments in a particular field. Perhaps your topic is historical and currency means the past hundred years rather than the past one or two years. Use the CRAAP test, be knowledgeable about your topic, and you will be on your way to evaluating information efficiently and well!

Next, visit the ACC Library’s Website for a tutorial and quiz on using the CRAAP test to evaluate sources.

Developing Yourself As a Critical Thinker

Critical thinking is a fundamental skill for college students, but it should also be a lifelong pursuit. Below are additional strategies to develop yourself as a critical thinker in college and in everyday life:

- Reflect and practice: Always reflect on what you’ve learned. Is it true all the time? How did you arrive at your conclusions?

- Use wasted time: It’s certainly important to make time for relaxing, but if you find you are indulging in too much of a good thing, think about using your time more constructively. Determine when you do your best thinking and try to learn something new during that part of the day.

- Redefine the way you see things: It can be very uninteresting to always think the same way. Challenge yourself to see familiar things in new ways. Put yourself in someone else’s shoes and consider things from a different angle or perspective. If you’re trying to solve a problem, list all your concerns: what you need in order to solve it, who can help, what some possible barriers might be, etc. It’s often possible to reframe a problem as an opportunity. Try to find a solution where there seems to be none.

- Analyze the influences on your thinking and in your life: Why do you think or feel the way you do? Analyze your influences. Think about who in your life influences you. Do you feel or react a certain way because of social convention, or because you believe it is what is expected of you? Try to break out of any molds that may be constricting you.

- Express yourself: Critical thinking also involves being able to express yourself clearly. Most important in expressing yourself clearly is stating one point at a time. You might be inclined to argue every thought, but you might have greater impact if you focus just on your main arguments. This will help others to follow your thinking clearly. For more abstract ideas, assume that your audience may not understand. Provide examples, analogies, or metaphors where you can.

- Enhance your wellness: It’s easier to think critically when you take care of your mental and physical health. Try taking activity breaks throughout the day to reach 30 to 60 minutes of physical activity each day. Scheduling physical activity into your day can help lower stress and increase mental alertness. Also, do your most difficult work when you have the most energy. Think about the time of day you are most effective and have the most energy. Plan to do your most difficult work during these times. And be sure to reach out for help if you feel you need assistance with your mental or physical health (see Maintaining Your Mental and Physical Health for more information).

Complete ACTIVITY 1: REFLECT ON CRITICAL THINKING at the end of the chapter to deepen your understanding of critical thinking in action.

Creative Thinking

Creative thinking is an invaluable skill for college students because it helps you look at problems and situations from a fresh perspective. Creative thinking is a way to develop novel or unorthodox solutions that do not depend wholly on past or current solutions. It’s a way of employing strategies to clear your mind so that your thoughts and ideas can transcend what appears to be the limitations of a problem. Creative thinking is a way of moving beyond barriers and it can be understood as a skill—as opposed to an inborn talent or natural “gift”—that can be taught as well as learned.

However, the ability to think and act in creative ways is a natural ability that we all exhibited as children. The curiosity, wonder, imagination, playfulness, and persistence in obtaining new skills are what transformed us into the powerful learners that we became well before we entered school. As a creative thinker now, you are curious, optimistic, and imaginative. You see problems as interesting opportunities, and you challenge assumptions and suspend judgment. You don’t give up easily. You work hard. Is this you? Even if you don’t yet see yourself as a competent creative thinker or problem-solver yet, you can learn solid skills and techniques to help you become one.

Creative Thinking in Education

College is a great ground for enhancing creative thinking skills. The following are some examples of college activities that can stimulate creative thinking. Are any familiar to you? What are some aspects of your own college experience that require you to think creatively?

- Design sample exam questions to test your knowledge as you study for a final.

- Devise a social media strategy for a club on campus.

- Propose an education plan for a major you are designing for yourself.

- Prepare a speech that you will give in a debate in your course.

- Arrange audience seats in your classroom to maximize attention during your presentation.

- Participate in a brainstorming session with your classmates on how you will collaborate on a group project.

- Draft a script for a video production that will be shown to several college administrators.

- Compose a set of requests and recommendations for a campus office to improve its services for students.

- Develop a marketing pitch for a mock business you are developing.

- Develop a plan to reduce energy consumption in your home, apartment, or dorm.

How to Stimulate Creative Thinking

The following video, How to Stimulate the Creative Process, identifies six strategies to stimulate your creative thinking.

- Sleep on it. Over the years, researchers have found that the REM sleep cycle boosts our creativity and problem-solving abilities, providing us with innovative ideas or answers to vexing dilemmas when we awaken. Keep a pen and paper by the bed so you can write down your nocturnal insights if they wake you up.

- Go for a run or hit the gym. Studies indicate that exercise stimulates creative thinking, and the brainpower boost lasts for a few hours.

- Allow your mind to wander a few times every day. Far from being a waste of time, daydreaming has been found to be an essential part of generating new ideas. If you’re stuck on a problem or creatively blocked, think about something else for a while.

- Keep learning. Studying something far removed from your area of expertise is especially effective in helping you think in new ways.

- Put yourself in nerve-racking situations once in a while to fire up your brain. Fear and frustration can trigger innovative thinking.

- Keep a notebook with you, or create a file for ideas on your smartphone or laptop, so you always have a place to record fleeting thoughts. They’re sometimes the best ideas of all.

The following video, Where Good Ideas Come From by Steven Johnson, reinforces the idea that time allows creativity to flourish.

Watch this supplemental video by PBS Digital Studies: How To Be Creative | Off Book | PBS Digital Studio for a more in-depth look on how to become a “powerful creative person.”

Below is an article by Professor Tobin Quereau, called In Search of Creativity. Perhaps the article can help you think about some simple principles that can enhance your own creative thinking.

In Search of Creativity

Tobin Quereau

As I was searching through my files the other day for materials on creativity, I ran across some crumpled, yellowed notes which had no clear identification as to their source. Though I cannot remember exactly where they came from, I pass them along to you as an example of the absurd lengths to which some authors will go to get people’s attention.

The notes contained five principles or practices with accompanying commentary which supposedly enhance creativity. I reprint them here as I found them and leave you to make your own judgment on the matter....

1. Do It Poorly! One has to start somewhere and hardly anyone I know starts perfectly at anything. As a result, hardly anyone seems to start very much at all. Often times the quest for excellence quashes any attempt at writing, thinking, doing, saying, etc., since we all start rather poorly in the beginning. Therefore, I advocate more mediocrity as a means to success. Whatever you want, need, or have to do, start doing it! (Apologies to Nike, but this was written long before they stole the concept....) Do it poorly at first with pleasure, take a look or listen to what you’ve done, and then do it again. If you can turn out four good, honest, poor quality examples, the fifth time you should have enough information and experience to turn out something others will admire. And if you do the first four tries in private, only you need to know how you got there.

2. Waste Time! Don’t spend it all doing things. Give yourself time and permission to daydream, mull over, muse about your task or goal without leaping into unending action. “But what,” you say, “if I find myself musing more about the grocery shopping than the gross receipts?” Fine, just see what relationships you can come up with between groceries and gross receipts. (How about increasing the volume and lowering mark-ups? Or providing comfortable seating in the local superstore so that people can relax while shopping and thus have more energy with which to spend their money??) Whatever you do, just pay attention to what comes and get it down in writing somewhere somehow before it goes again. No need to waste ideas....

3. Be Messy! (Not hard for some of us.) Don’t go for clarity before confusion has had time to teach you something new. In fact, I advocate starting with a large sheet of blank paper–anything up to 2 feet by 4 feet in size–and then filling it up as quickly and randomly as possible with everything that is, might be, or ought to be related to the task at hand. Then start drawing arrows, underlining, scratching through, highlighting, etc., to make a real mess that no one but you can decipher. (If you can’t figure it out either, that’s O.K., too–it doesn’t have to make sense in the beginning.) Then go back to Principle #1 and start doing something.

4. Make Mistakes! Search out your stumbling blocks. Celebrate your errors. Rejoice in your “wrongs” for in them lie riches. Consider your faux pas as feedback not failure and you’ll learn (and possibly even earn!) a lot more. Be like a research scientist and get something publishable out of whatever the data indicates. As one creative consultant, Sidney X. Shore, suggests, always ask, “What’s Good About It?” Some of our most precious inventions have resulted from clumsy hands and creative insight.

5. Forget Everything You Have Learned! (Except, perhaps, these principles!) Give yourself a chance to be a neophyte, return to innocence, start with “beginner’s mind”. In the Zen tradition of Japan, there is a saying in support of this approach because in the beginner’s mind all things are possible, in the expert’s mind only one or two. What would a five-year-old do with your task, goal, project, or problem? Take a risk and be naive again. Many major advances in math and science have come from young, wet-behind-the-ears upstarts who don’t know enough to get stuck like everyone else. Even Picasso worked hard at forgetting how to draw....

But I must stop! There was more to this unusual manuscript, but it would be a poor idea to prolong this further. As a responsible author, I don’t want to waste any more of your time on such ramblings. You know as well as I that such ideas would quickly make a mess of things. I am sure that the original author, whoever that was, has by now repudiated these mistaken notions which could be quite dangerous in the hands of untrained beginners. I even recall a reference to these principles being advocated for groups and teams as well as for individual practice—if you can imagine such a thing! It is a pity that the author or authors did not have more to offer, however, “In Search of Creativity” could have made a catchy title for a book....

Problem Solving with Creative Thinking

Creative problem-solving is a type of problem-solving that involves searching for new and novel solutions to problems. It’s a way to think “outside of the box.” Unlike critical thinking, which scrutinizes assumptions and uses reasoning, creative thinking is about generating alternative ideas— practices and solutions that are unique and effective. It’s about facing sometimes muddy and unclear problems and seeing how things can be done differently.

Complete ACTIVITY 2: ASSESS YOUR CREATIVE-PROBLEM SOLVING SKILLS at the end of the chapter to see what skills you currently have and which new ones you can develop further.

As you continue to develop your creative thinking skills, be alert to perceptions about creative thinking that could slow down progress. Remember that creative thinking and problem-solving are ways to transcend the limitations of a problem and see past barriers.

| FICTION | FACTS |

1 | Every problem has only one solution (or one right answer) | The goal of problem-solving is to solve the problem, and most problems can be solved in any number of ways. If you discover a solution that works, it’s a good solution. Other people may think up solutions that differ from yours, but that doesn’t make your solution wrong or unimportant. What is the solution to “putting words on paper?” Fountain pen, ballpoint, pencil, marker, typewriter, printer, printing press, word-processing… all are valid solutions! |

2 | The best answer, solution, or method has already been discovered | Look at the history of any solution and you’ll see that improvements, new solutions, and new right answers are always being found. What is the solution to human transportation? The ox or horse, the cart, the wagon, the train, the car, the airplane, the jet, the space shuttle? What is the best and last? |

3 | Creative answers are technologically complex | Only a few problems require complex technological solutions. Most problems you’ll encounter need only a thoughtful solution involving personal action and perhaps a few simple tools. Even many problems that seem to require technology can be addressed in other ways. |

4 | Ideas either come or they don’t. Nothing will help— certainly not structure. | There are many successful techniques for generating ideas. One important technique is to include structure. Create guidelines, limiting parameters, and concrete goals for yourself that stimulate and shape your creativity. This strategy can help you get past the intimidation of “the blank page.” For example, if you want to write a story about a person who gained insight through experience, you can stoke your creativity by limiting or narrowing your theme to “a young girl in Cambodia who escaped the Khmer Rouge to find a new life as a nurse in France.” Apply this specificity and structure to any creative endeavor. |

Critical and creative thinking complement each other when it comes to problem-solving. The process of alternatively focusing and expanding your thinking can generate more creative, innovative, and effective outcomes. The following words, by Dr. Andrew Robert Baker, are excerpted from his “Thinking Critically and Creatively” essay. Dr. Baker illuminates some of the many ways that college students will be exposed to critical and creative thinking and how it can enrich their learning experiences.

THINKING CRITICALLY AND CREATIVELY

Critical thinking skills are perhaps the most fundamental skills involved in making judgments and solving problems. You use them every day, and you can continue improving them.

The ability to think critically about a matter—to analyze a question, situation, or problem down to its most basic parts—is what helps us evaluate the accuracy and truthfulness of statements, claims, and information we read and hear. It is the sharp knife that, when honed, separates fact from fiction, honesty from lies, and the accurate from the misleading. We all use this skill to one degree or another almost every day. For example, we use critical thinking every day as we consider the latest consumer products and why one particular product is the best among its peers. Is it a quality product because a celebrity endorses it? Because a lot of other people may have used it? Because it is made by one company versus another? Or perhaps because it is made in one country or another? These are questions representative of critical thinking.

The academic setting demands more of us in terms of critical thinking than everyday life. It demands that we evaluate information and analyze myriad issues. It is the environment where our critical thinking skills can be the difference between success and failure. In this environment we must consider information in an analytical, critical manner. We must ask questions—What is the source of this information? Is this source an expert one and what makes it so? Are there multiple perspectives to consider on an issue? Do multiple sources agree or disagree on an issue? Does quality research substantiate information or opinion? Do I have any personal biases that may affect my consideration of this information?

It is only through purposeful, frequent, intentional questioning such as this that we can sharpen our critical thinking skills and improve as students, learners and researchers.

While critical thinking analyzes information and roots out the true nature and facets of problems, it is creative thinking that drives progress forward when it comes to solving these problems. Exceptional creative thinkers are people that invent new solutions to existing problems that do not rely on past or current solutions. They are the ones who invent solution C when everyone else is still arguing between A and B. Creative thinking skills involve using strategies to clear the mind so that our thoughts and ideas can transcend the current limitations of a problem and allow us to see beyond barriers that prevent new solutions from being found.

Brainstorming is the simplest example of intentional creative thinking that most people have tried at least once. With the quick generation of many ideas at once, we can block-out our brain’s natural tendency to limit our solution-generating abilities so we can access and combine many possible solutions/thoughts and invent new ones. It is sort of like sprinting through a race’s finish line only to find there is new track on the other side and we can keep going, if we choose. As with critical thinking, higher education both demands creative thinking from us and is the perfect place to practice and develop the skill. Everything from word problems in a math class, to opinion or persuasive speeches and papers, call upon our creative thinking skills to generate new solutions and perspectives in response to our professor’s demands. Creative thinking skills ask questions such as—What if? Why not? What else is out there? Can I combine perspectives/solutions? What is something no one else has brought-up? What is being forgotten/ignored? What about ______? It is the opening of doors and options that follows problem-identification.

Consider an assignment that required you to compare two different authors on the topic of education and select and defend one as better. Now add to this scenario that your professor clearly prefers one author over the other. While critical thinking can get you as far as identifying the similarities and differences between these authors and evaluating their merits, it is creative thinking that you must use if you wish to challenge your professor’s opinion and invent new perspectives on the authors that have not previously been considered.

So, what can we do to develop our critical and creative thinking skills? Although many students may dislike it, group work is an excellent way to develop our thinking skills. Many times I have heard from students their disdain for working in groups based on scheduling, varied levels of commitment to the group or project, and personality conflicts too, of course. True—it’s not always easy, but that is why it is so effective. When we work collaboratively on a project or problem we bring many brains to bear on a subject. These different brains will naturally develop varied ways of solving or explaining problems and examining information. To the observant individual we see that this places us in a constant state of back and forth critical/creative thinking modes.

For example, in group work we are simultaneously analyzing information and generating solutions on our own, while challenging other’s analyses/ideas and responding to challenges to our own analyses/ideas. This is part of why students tend to avoid group work—it challenges us as thinkers and forces us to analyze others while defending ourselves, which is not something we are used to or comfortable with as most of our educational experiences involve solo work. Your professors know this—that’s why we assign it—to help you grow as students, learners, and thinkers!

—Dr. Andrew Robert Baker, Foundations of Academic Success: Words of Wisdom

Problem-Solving Action Checklist

Problem-solving can be an efficient and rewarding process, especially if you are organized and mindful of critical steps and strategies. Remember to assume the attributes of a good critical thinker: if you are curious, reflective, knowledge-seeking, open to change, probing, organized, and ethical, your challenge or problem will be less of a hurdle, and you’ll be in a good position to find intelligent solutions. The steps outlined in this checklist will help you adhere to these qualities in your approach to any problem:

| STRATEGIES | ACTION CHECKLIST | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Define the problem |

|

| 2 | Identify available solutions |

|

| 3 | Select your solution |

|

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Critical thinking is logical and reflective thinking focused on deciding what to believe or do.

- Critical thinking involves questioning and evaluating information.

- Evaluating information is a complex, but essential, process. You can use the CRAAP test to help determine if sources and information are reliable.

- Creative thinking is both a natural aspect of childhood and a re-learnable skill as an adult.

- Creative thinking is as essential a skill as critical thinking and integrating them can contribute to innovative and rewarding experiences in life.

- Critical and creative thinking both contribute to our ability to solve problems in a variety of contexts.

- You can take specific actions to develop and strengthen your critical and creative thinking skills.

ACTIVITY 1: REFLECT ON CRITICAL THINKING

Objective

- Apply critical thinking strategies to your life

Directions:

- Think about someone you consider to be a critical thinker (friend, professor, historical figure, etc). What qualities does he/she have?

- Review some of the critical thinking strategies discussed on this page. Pick one strategy that makes sense to you. How can you apply this critical thinking technique to your academic work?

- Habits of mind are attitudes and beliefs that influence how you approach the world (i.e., inquiring attitude, open mind, respect for truth, etc). What is one habit of mind you would like to actively develop over the next year? How will you develop a daily practice to cultivate this habit?

- Write your responses in journal form, and submit according to your instructor’s guidelines.

ACTIVITY 2: ASSESS YOUR CREATIVE PROBLEM-SOLVING SKILLS

Directions:

- Access Psychology Today’s Creative Problem-Solving Test at the Psychology Today Web site.

- Read the introductory text, which explains how creativity is linked to fundamental qualities of thinking, such as flexibility and tolerance of ambiguity.

- Then advance to the questions by clicking on the “Take The Test” button. The test has 20 questions and will take roughly 10 minutes.

- After finishing the test, you will receive a Snapshot Report with an introduction, a graph, and a personalized interpretation for one of your test scores.

Complete any further steps by following your instructor’s directions.

LICENSES AND ATTRIBUTIONS

LICENSES AND ATTRIBUTIONS

CC LICENSED CONTENT, ORIGINAL

- Critical and Creative Thinking Authored by: Laura Lucas, Tobin Quereau, and Heather Syrett. Provided by: Austin Community College. License: CC BY-NC-SA-4.0

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SPECIFIC ATTRIBUTION

- Chapter cover image. Authored by: Hans-Peter Gauster. Provided by: Unsplash. Located at: https://unsplash.com/photos/3y1zF4hIPCg. License: CC0: No Rights Reserved

- Image. Authored by: Mari Helin-Tuominen. Provided by: Unsplash. Located at: https://unsplash.com/photos/ilSnKT1IMxE. License: CC0: No Rights Reserved

- Critical Thinking Skills. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/collegesuccess-lumen/chapter/critical-thinking-skills/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Critical Thinking. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/educationalpsychology/chapter/critical-thinking/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Critical Thinking 101: Spectrum of Authority. Located at: https://youtu.be/9G5xooMN2_c. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Creative Thinking Skills. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/collegesuccess-lumen/chapter/creative-thinking-skills/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Evaluate: Assessing Your Research Process and Findings. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/informationliteracy/chapter/evaluate-assessing-your-research-process-and-findings/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Creative Thinking Skills. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/collegesuccess-lumen/chapter/creative-thinking-skills/. License: CC BY: Attribution

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED CONTENT

- Where Good Ideas Come From. Authored by: Steven Johnson. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NugRZGDbPFU. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- How to Stimulate the Creative Process. Authored by: Howcast. Located at: https://youtu.be/kPC8e-Jk5uw. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube License